Towards A New (Unilateral) Bretton Woods: Fair Global Trade

The Trump administration’s new tariff deal with China is a partial climbdown. USTR Jamieson Greer says the U.S. effective average tariff rate on China will now be around 55%.

High tariffs on China are entirely justified. China has been destabilizing the world trading system for 30 years with its overproduction and excessive trade surpluses. It began with basic industries like steel and chemicals and has now expanded into advanced manufacturing sectors like robotics and microchips.

I want to present the case for a global system of trade relations that would establish an objective standard and stand a good chance of winning the support of many other nations. I call it Fair Global Trade.

Fair Global Trade (FGT) is nothing like the woolly concepts of “fair trade” used by activist groups to criticize various labor practices or health standards or other subjective values-based concepts. This is a proposal to lay out a couple of simple rules of the road, based on objective trade data, for what constitutes acceptable trade and when trade becomes unfair, and secondly for the U.S. to make tariff policies to enforce those preferences. I think these rules are so self-evidently in the interest of not just the U.S. but the majority of nations, that if we were to announce them, we would find other nations adopting them alongside us.

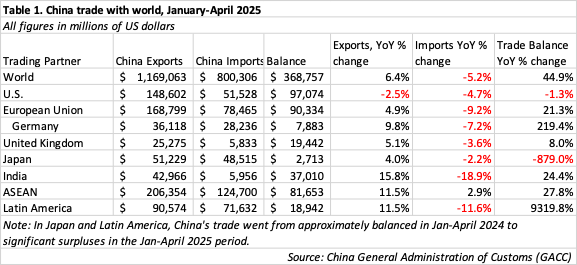

First, a closer look at China’s trade in the first four months of 2025. The data, from the Chinese government, demonstrate clearly that China has no interest in balanced trade.

Chinese exports in April were up 8.1% over April 2024. For the first four months of the year, China’s exports were up 6.4%. As Table 1 shows, exports to the U.S. fell 2.5%. But they rose 4.9% to the European Union, 9.8% to Germany, and 15.8% to India. Of course, some of these increases are due to new circuitous trade routes to the U.S. The increase in exports to Vietnam (18.1%) and Thailand (20.6%) likely reflect this rerouting. After all, U.S. goods imports in the first three months of 2025 were up 26.2% over the corresponding period in 2024, reflecting U.S. importers trying to beat the expected Trump tariffs, as well as continued strong consumer spending in the U.S.

Globally, China ran a goods surplus with the world of $368 billion in the first four months of this year. That’s an annual rate of $1.1 trillion, roughly 1% of global GDP. That’s a huge surplus for any one nation to run. Five years ago, a trillion dollar surplus would have been unthinkable. For many nations, trade with China, which was already unbalanced before the Covid pandemic, just gets more and more unbalanced. For example, while Chinese exports to the EU rose 4.9% in the first four months of this year, Chinese imports from the EU fell by 9.2%. For India, Chinese exports rose 15.8% while its imports from India fell by 18.9%. For Latin America, Chinese exports rose by 11.5% while its imports from Latin America fell by 11.6%. Those weak import figures are the result of a weak domestic Chinese economy but also China’s deliberate policy of breeding domestic Chinese companies to replace the need for foreign imports.

China is the world’s second largest economy, accounting for some 17% of global GDP. China’s export-led growth of the late 90s and early 2000s has now morphed into a desire for global domination of many key industries, a plan explicitly spelled out in the famous “Made in China 2025.” As a Communist dictatorship, it has managed the Chinese economy to hold down wages and use government and bank sector funds to massively subsidize its industries to drive foreign competitors out of business and consolidate its own leadership. In contrast, Japan and the Asian tigers all have some degree of democracy and allowed the prosperity of their export industries to flow through to workers and indeed their entire economies. The combination of all these trade surpluses now puts an unbearable burden on the world economy. Trade can only survive if there is some pressure for every nation to gravitate towards balance (as the system functioned quite effectively under the gold standard, pre-1914).

The U.S. can restore that pressure towards balance with Fair Global Trade (FGT).

The U.S. consumer market is the world’s most coveted market. Each year we import $3 trillion of goods. Every economic model I and my colleagues have built show that any level of tariffs or dollar devaluation or other policy tool would not suppress those imports below around about $2.5 trillion. If you are a foreign producer, whether you are selling children’s dolls, or airplanes, or industrial pumps, the market you want to break into is the U.S. market.

The U.S. could leverage its position as the world’s customer of choice into a new global regime for Fair Global Trade. It could announce that persistent trade surpluses are “beggar-thy-neighbor” anti-social economic policies and would henceforth be penalized in the U.S. with high tariffs. Trade surpluses are bad when they are too large in absolute (i.e. dollar) terms and when they are too large in terms of share of GDP of the nation running them.

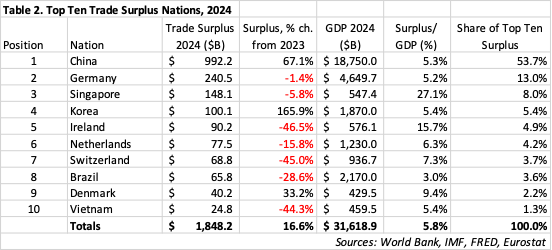

Table 2 shows the ten largest trade surplus countries in the world, based on data from the World Bank and national statistical agencies. The thresholds should be chosen with care, but as a first run at the proposal, I suggest we say that any trade surplus that is persistent and over $50 billion and over 3% of that nation’s GDP is anti-social and warrants FGT measures.

The policy has to bite. I suggest a 50% tariff on all imports from any country above the thresholds. The tariff would persist until a nation turned in a full year’s trade data showing it was under the threshold. I have omitted all countries whose trade surplus stems from primary products. This removes Saudi Arabia, Norway, Angola, and several other oil states from the list. Countries should not be penalized for the riches that nature bestowed upon them, and which the world needs to buy as cheaply as possible. This leaves us with China, Germany, Ireland, the Netherlands, and Vietnam as some of the leading anti-social nations.

Furthermore, the U.S. should announce that it would like to recruit other nations to join the FGT community. Today President Trump appears committed to a 10% baseline tariff. An alternative would be to have a baseline 20% tariff but a special “FGT community” tariff of either 10%, 5% or even 0% for all nations who join the community and agree to levy 50% tariffs on anti-social nations. Such a tariff structure would likely generate several hundred billion dollars for the U.S. Treasury, pleasing Republicans who want to cut taxes and use tariff revenue for some of the financing.

Consider the impact an American FGT policy have on a country like Germany. Today it is anti-social by the FGT definition. Germany has run trade surpluses for years. But the appeal of the U.S. market could be strong enough for Germany to decide that it should target reducing its trade surplus to $50 billion, and joining the U.S. in levying a 50% tariff on imports from China. Germany is beginning to wake up to the fact that its trading relationship with China is steadily worsening. Last year, Germany ran a $72 billion deficit with China.

This policy could fairly rapidly build a broad FGT community of fair trading nations and isolate China. That’s one of the aims of the policy. The world trading system cannot survive one nation that runs a persistent $1 trillion trade surplus and seeks to become completely self-sufficient in crucial industries like microchips and dominate global production in other industries like rare earths. If the U.S. can win over other nations to join the FGT community, its economic power will grow. It could eventually evolve into a formal international agreement, a genuine new Bretton Woods.

And there is another positive aspect to such a plan. The U.S. corporate sector is still very much divided about globalization, and generally opposed to tariffs. By giving trade policy a rational, objective basis, the government could win over the recalcitrant corporate sector. Over time, this would be good for the American middle class and American workers, by reducing the worst of the subsidized low-wage competition. We would effectively decouple from China and any other persistent beggar-thy-neighbor countries, while preserving trade relations with other emerging market nations.

Don’t get me wrong. This won’t solve all of America’s economic problems. The U.S. has plenty of domestic economic problems to resolve to get back onto a high-growth path. For a start, the U.S. needs get more competitive in manufacturing, and spread the benefits of our world-leading sectors more broadly throughout the population. But a Fair Global Trading regime would be a great start, and go some way towards rebuilding the global environment of the 1950s and 1960s that was conducive to international growth.

Jeff, may I suggest you enable voice-over on this thing? I like to listen to Substack while walking my dog.